Bryn Myrddin, Marlyn, Melior, Mellin, Mellins, Merdhin, Merlin Ambrosius, Merlin Sylvester, Merlino, Merlins, Merlion, Merlinus, Merlun, Merlyn, Merlyng, Myrddin, Myrrdin

Merlin… the very name conjures up images of magic and mystery. And what a mystery. Perhaps even more than King Arthur, the real character and person of Merlin remains obscure, lost in fifteen centuries of tales retold. But as a creature of the imagination Merlin lives on, and will forever. We all love to dream, and in Merlin we have the forefather of all our dreams, the master of enchantments, the prophet and kingmaker. To Merlin, the all-seeing, the all-knowing, nothing was impossible. Merlin is the root and branch of all that is magic and wonder in the world.

Merlin’s Origin | Merlin, Uther Pendragon and Arthur’s Birth | Merlin’s Entertainments | The Necromancer | The Real Merlin? | Tomb of Merlin | Literary Origins | The Name Merlin

Merlin’s Origin

According to a tradition not found in Malory, but very likely familiar to Malory’s readers, Merlin was engenderd, despite all precautions, by a fiend on a woman who had been trying to remain pure.

At her trial, the infant Merlin himself revealed who was his father and made a few other prophecies and revelations, at least one of them rather embarrassing to the judges. Some say the father of Merlin was a demon of air (incubus) and he was raised in a nunnery. Robert says the devils of Hell had determined to set on earth an evil being to counterbalance the good introduced by Jesus Christ. Happily, the child was promptly baptized so he was not evil!

Even in Malory’s account, Merlin is occasionally called a devil’s son, and now and then a medieval romancer throws in a comment to the effect that, although usually regarded as beneficent, Merlin is really evil.

In all fairness, however, one must point out a remark in Vulgate II that, while Merlin owed his knowledge of the past to the Devil, he owed his knowledge of the future to the Lord.

Again, Vulgate II tells us that Merlin never laid his hands upon anyone, though with his power, he hardly needed to be physical! Vulgate II contains a statement that he was “treacherous and disloyal by nature” and mentions a stone at which he slew two other enchanters.

Merlin’s mother was called Aldan in Welsh tradition, Optima in French romance and Marinaia in Pieri’s Storia di Merlino (fourteenth century). The Elizabethan play The Birth of Merlin – which may have been partially authored by Shakespeare – calls her Joan Goto-‘t.

That he had no father does not seem to be a feature of Welsh tradition. He was also said to be the son of Morgan Frych who, some claimed, had been a prince of Gwynedd.

Merlin, Uther Pendragon and Arthur’s Birth

Vortigern, King of Britain some time after the Roman withdrawal, was haplessly trying to build a new tower for, whenever it was erected, it would collapse. The king’s counsellors told he would need to sacrifice a fatherless child to remedy this. Such children were hardly thick on the ground but Merlin, now a youth, was popularly supposed to be sireless so he was secured for this purpose.

However, he pointed out that the real reason for the collapse was the existence of a pool beneath the foundations. Digging revealed the truth of this and a brace of dragons emerged, one red and one white; these caused Merlin to utter a series of prophecies. Merlin then left to study magic from Blaise, while Vortigern went on to be killed by the sons of Constans, as per Merlin’s prophecy.

Outstripping his master in necromantic learning, Merlin swore never to do Blaise harm and asked him to write a book. Blaise retired into the Forest of Northumberland to write down the doings of his former student. Here Merlin used to visit him from time to time.

When Constans’ son, King Pandragon, was killed by the Sesnes, Merlin brought the stones of Stonehenge from Ireland to serve as his tomb. (I’ve read that Aurelius Ambrosius defeated Vortigern and wished to put up a monument. Merlin advised him to make an expedition to Ireland to produce certain stones and these were erected on Salisbury Plain as Stonehenge.) Merlin then became advisor to the new king, Pandragon’s brother Uther, now surnamed Pendragon in honor of the late king.

To Uther Merlin revealed the mysteries of the two holy tables – the one Christ and His disciples used at the Last Supper and the one Joseph of Arimathea and his followers set up when they came to Britain. Merlin erected the third great table, the Round Table, for Uther at Cardoel in Wales (from where it passed into the keeping of Leodegrance and thence to Arthur).

Uther conceiving a lust for the duchess Igraine of Tintagil, Merlin played his pander, magically giving Uther the appearance of the lady’s husband Gorloïs, so that she lay with him unsuspecting. After the apparently coincidental death of Gorloïs, Uther married Igraine.

Soon came Merlin unto the king, and said, Sir, ye most purvey you for the nourishing of your child. As thou wilt, said the king, be it. Well, said Merlin, I know a lord of yours in this land... and he shall have the nourishing of your child,, and his name is Sir Ector... let him be sent for, for to come and speak with you ... And when the child is born let it be delivered to me at yonder privy postern unchristened... Then when the lady was delivered, the king commanded two knights and two ladies to take the child, bound in a cloth of gold, and that ye deliver him to what poor man ye meet at the postern gate of the castle. So the child was delivered unto Merlin.

Those modern romancers who stick to some recognizable variant of this episode have exercised considerable ingenuity to explain Merlin’s motives for taking Arthur and giving him to Ector with so much secrecy – not even Igraine was told where her child was taken. Tennyson came up with the most plausible explanation I’ve yet encountered, but he had to kill off Uther on the same night of Arthur’s birth to do it.

Returning to Malory, I cannot help but wonder why and how it should have been for the good of Arthur and the kingdom to raise the heir in such secrecy. Uther married Igraine so soon after Gorloïs’ death that by the rules of the milieu Arthur should have been recognized easily as Uther’s legal son and heir; at any rate, the whole explanation was accepted by enough of the kingdom to give Arthur a following when Merlin finally gave it years later. Why should it not have been equally well accepted at once? Malory’s Uther survived for at least two years after Arthur’s birth, and after his death his widow seems to have been left unmolested, even though the realm was thrown into confusion for lack of visible heir. If there had been a visible heir, a son known to be of Uther’s marriage, would the child really have run a great risk of assassination, surrounded as he would have been by barons? Would not Igraine or some strong baron simply have been named regent until his majority? Merlin arranged the famous test of the Sword in the Stone and had Arthur crowned king on the strength of this test alone, and the senstiment of the

commons ... both rich and poor.

Under such circumstances, how blameworthy were those rebel kings and barons who refused to yield their allegiance at once to an unknown, unproven youth, the protégé of a devil’s son? True, when the rebels gave Arthur their challenge, Merlin made them a bald statement, with no supporting evidence, of Arthur’s birth; it seems hardly suprising that

some of them laughed him to scorn, as King Lot; and more other called him a witch.

Nor had Merlin yet told Arthur himself of his parentage, which omission resulted in the incesuous begetting of Mordred on Margawse. Not until after the battle of Bedegraine – a slaughter so bloody it seems to have disgusted Merlin himself, who had helped engineer Arthur’s victory by bringing the army of kings Ban and Bors swiftly and secretly to the place – did Merlin reveal Arthur’s parentage, with some supporting evidence, to Arthur and the assembled court, in a scene that suggests a practical joke played by Merlin on Igraine to give her an additional moment of grief before restoring her to her son. In this scene Sir Ulfius, a former knight of Uther’s and his companion in the abduction of Igraine at Tintagil, as well as Merlin’s seeming accomplice (though perhaps unaware) in the “joke” on Igraine, himself stated that “Merlin is more to blame than” Igraine for the wars of the rebellion.

Perhaps the key to why Merlin wished to arrange Arthur’s upbringing lies in the word “unchristened”. Was Arthur ever christened, or did Ector, on receiving him, assume that Uther had seen to that point? It seems heretical to suggest it, but did Merlin wish to make of Arthur his own pawn and tool?

Merlin’s Entertainments

According to Haywood’s Life of Merlin Vortigern became subject to melancholy and, to cheer him up, Merlin provided various entertainments, such as invisible musicians and flying hounds chasing flying hares.

The Necromancer

Merlin did considerable traveling on the Continent, most of it, one supposes, during the years when Sir Ector was raising Arthur (although some of it may also have been in the years between Vortigern’s death and Pandragon’s). One of his continental adventures may be found under Avenable. Surprisingly, Merlin also dabbled in Christian missionary work, converting King Flualis of Jerusalem and his wife; this royal couple had four daughters, who in turn had fifty-five sons, all good knights, and these went forth to convert the heathen; some of them reached Arthur’s court. It may also have been during this period that Merlin met Viviane, fell in love with her, and taught her his crafts in return for the promise of her love.

It would be difficult and tedious to list every deed and prophecy of Merlin’s; one does not envy Blaise his task. The Great Necromancer could prophecy anything – though fairly early in his career, before Arthur’s birth, he decided to phrace his prophecies in obscure terms. He could apparently do anything within the scope of necromancy, except break the spell that was his downfall.

He must have made rather a pest of himself with his disguises, popping up as toddler, beggar, blind minstrel, stag, and so on, and so on, usually for no apparent reason. Indeed he seems to have had the temperament of a practical joker. Some of his prophecies may well have been more mischievous than useful. He entered the battlefield with Arthur and his armies, and does seem to have given them invaluable help, but one of Merlin’s pastimes in battle was moving around the field and telling the King and his knights, every time they took a short break from doing realy tremendous deeds of arms and valor, what cowards they were and how disgracefully they were carrying on. (Maybe that was Merlin’s style of cheerleading.)

Merlin may not have counseled Arthur to destroy the May babies, Herod-like, but he certainly sowed the seed of that sin by telling Arthur that one of these babies would be the King’s destruction, and he appears not to have lifted his voice against the mass slaughter. In all fairness, we must remember that he did warn Arthur against marrying Guenevere, foretelling her affair with Lancelot, and Arthur ignored his advice in that instance. (But did Merlin thus implant the suspicion that finally erupted in Arthur’s vengeful rage?)

Merlin engineered Arthur’s acquisition of Excalibur, sword and sheath, but in this mage apparently acted in unison with Malory’s first British Lady of the Lake, who was later revealed, by the sincere though unfortunate Balin le Savage, to have been very wicked; it is noticable that Merlin, when he learned of Balin’s accusation, did not defend his slain cohort by denying the charge, nor rail against Balin for killing her, but only replied with a countercharge against the damsel “Malvis.”

For all his foresight, Merlin had a habit of arriving just a little too late to do the most good. We know he was capable of very rapid travel, yet he let Balin lie beneath the ruins of Pellam’s castle for three days before coming to rescue him, by which time Balin’s damsel (Sir Herlews’ lady) was dead. Later he showed up the morning after the deaths of Balin and Balan, just in time to write their names on their tomb. He delivered King Meliodas of Lyonesse from the enchantress’ prison the morning after the death of Meliodas’ wife – had Merlin arrived a few days earlier, the brave and devoted Elizabeth would not have died.

Although from the above Merlin would appear something of a misogynist, he could hardly have been insensitive to a beautiful face. He did not spend all his time at Arthur’s court, and during one of his absences he taught Morgan le Fay necromancy in Bedingran (Bedegraine). According to Malory, Merlin became infatuated by Nimue (elsewhere called Viviane), whom he taught magical secrets which she used to imprison him.

Geoffrey, however, has him active after Camlann, bringing the wounded Arthur to Avalon. He then went mad after the battle of Arthuret and became a wild man, living in the woods. According to Giraldus Cambrensis, this was because of some horrible sight he beheld in the sky during the fighting. He had been on the side of Rhydderch Hael, King of Cumbria, who was married to Merlin’s sister, Ganieda, and three of Merlin’s brothers had died in the battle. After a time, Ganieda persuaded Merlin to give up his life in the forest, but he revealed to Rhydderch that she had been unfaithful to him. Merlin decided to return to the greenwood and urged his wife Guendoloena to remarry. However, his madness once again took hold of him and he turned up at the wedding, riding a stag and leading a herd of deer. In his rage, he tore the antlers from the stag and flung them at the bridegroom, killing him. He went back to the woods and Ganieda built him an observatory from which he could study the stars.

Welsh poetry antedating Geoffrey largely agrees with this account, though it has Merlin fighting against Rhydderch rather than for him. Similar tales are told about a character called Lailoken, who was in Rhydderch’s service and this may have prompted Geoffrey to change the side which Merlin was on. As Lailoken is similar to a Welsh word meaning ‘twin brother’ and as Merlin and Ganieda were thought to be twins, it is possible it was merely a nickname applied to Merlin. Merlin is not, at any rate, a personal name but a place name – the Welsh Myrddin comes from Celtic Maridunon (Carmarthen) – which was applied to the magician because, according to Geoffrey, he came from that city. Elsewhere it is averred that the city was founded by, and named after, the wizard. Robert has him born in Brittany. Geoffrey makes him King of Powys, and the idea that he was of royal blood is also found in Strozzi’s Venetia edificata (1624).

Further snippets of information found elsewhere are that he saved Tristan when he was a baby; that he had a daughter called La Damosel del Grant Pui de Mont Dolerous; that he was not imprisoned by Nimue but retired voluntarily to an esplumeor or place of confinement. At various times, Bagdemagus and Gawaine passed near his tomb and spoke with him; perhaps others did as well. Gawaine seems to have been the last to hear his voice.

Both Welsh poetry and Geoffrey have him speaking with Taliesin, with whom he seemed to be considerably connected in the Welsh mind. Thus one Welsh tradition asserted he first appeared in Vortigern’s time, then was reincarnated as Taliesin and reincarnated once more as Merlin the wild man. The idea that there were two Merlins, wizard and wild man, is found in Giraldus Cambrensis (the Norman-Welsh chronicler of the twelfth century), doubtless because of the impossibly long lifespan assigned to him by Geoffrey.

The Italian romances provide yet more tales about him – that he uttered prophecies about the House of Hohenstaufen and that he was charged (unsuccessfully) with heresy by a bishop called Conrad. Boiardo (an Italian poet) said Merlin made a fountain for Tristan to drink from so he would forget Iseult (Isolde of Cornwall), but Tristan never found it. According to Ariosto his soul was in a tomb. The soul informed the female warrior Bradmante that the House of Este would descend from her. According to Strozzi he lived in a cave when Attila the Hun invaded Italy and, while there, invented the telescope. The historian Godfried of Viterbo claimed he was an Anglo-Saxon.

A modern relic of the Merlin legend was to be found in the pilgrimages made to Merlin’s Spring at Barenton in Brittany, but these were stopped by the Vatican in 1853.

Merlin’s ghost is said to haunt Merlin’s Cave at Tintagel. The wizard is variously said to be buried at Drumelzier in Scotland, under Merlin’s Mount in the grounds of Marlborough College, at Mynydd Fyrddin and in Merlin’s Hill Cave in Carmarthen.

See also

Byanne | The Legend of King Arthur

The Real Merlin?

Like Arthur’s, Merlin’s story becomes entwined with a number of recorded historical events that may at least give us a starting point to identify when he lived. We are told that he was about eight or nine when Vortigern’s soldiers found him, and this followed the Saxon invasion of Britain under Hengist. Hengist’s arrival in Britain is usually dated to about 449 AD.

Just to set it in context, it might be useful to check out how that date relates to others who were living near or at that time, and who are likely to be better known. To be honest there aren’t many. We are really at the dawn of the Dark Ages. There was, though, S:t Patrick. Although his dates are uncertain it is probable that he arrived in Ireland sometime around 432 on his mission to convert the Irish to Christianity. He at length established a bishopric at Armagh around the year 454 and died around 461.

If Merlin existed, Patrick may well have known him or known of him. Attila the Hun was also alive. He had become king of the Huns in 434, and after ravaging most of easter Europe he invaded France in 451. The following year he invaded Italy and Rome itself was only saved by the intercession of the pope, Leo I, regarded as one of the greatest of the early popes.

This then was the period of Vortigern and Hengist. On Hengist’s arrival all at first went well. The Saxons aided Vortigern in the repulsion of the Picts and for a short period there was peace. Vortigern even married Hengist’s daughter, Reinwen (Rowena), to form an alliance. But Hengist now had a toe-hold on Britain and, in 455, he sent for further reinforcements. It would be at this time that Vortigern fled. How long he remained in the Welsh hills is uncertain, but we can imagine there were a few years before his death. The likely date for the first appearance of Merlin, therefore, is around 457 or 458, which would place his birth at about the year 450.

Geoffrey’s chronology becomes little truncated over the next events. Aurelianus and Uther return from Gaul almost immediately; Vortigern and Hengist are killed. In fact, for all the historical evidence of Hengist’s existence is sparse, he is believed to have ruled over his stronghold in Kent for at least thirty years and perished around the year 488, the date recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. In place of Geoffrey’s record we can envisage that Aurelianus fought back the Saxons from overrunning Britain and established an uneasy peace with Hengist’s men remaining in Kent, and Aurelianus having lordship over the rest of southern Britain.

Not much is known about Aurelianus, or Ambrosius Aurelianus (Aurelian the Divine) as he is sometimes called. He is believed to have been a descendant of a Roman family who sought to uphold the last vestiges of Roman civilization in Britain. He may well have been from a noble British family with Roman sympathies. He was certainly alive around 437 when he was involved in a battle at Guoloph, or Wallop, in Hampshire. The date of his death is uncertain but it was probably around the year 473, because it was then that the Saxons began again their incursions, which suggests that opposition to them had weakend.

Geoffrey of Monmouth, of course, now records Uther, called the Pendragon (or chief dragon or ruler), as king, and no doubt there was a successor to Aurelianus who sought to hold back the Saxons, though less successfully than his predecessor.

Uther must have ruled a few years before he succumed to be the beauty of Ygraine, though that period is not identified of Geoffrey. Allowing for some uncertainty over the dating of the death of Aurelianus, we could place Arthur’s conception at around 475. This is the date suggested by Norma Lorre Goodrich in her fascinating studies of the legend, King Arthur [1986] and Merlin [1988].

Geoffrey does tell us that Arthur was fifteen years old when Uther died, which would bring us to about the year 490, by which time Merlin would be about forty. Although a boy king may sustain the support of his people, he would still require a wise counsellor to help him in his judgements, and that would be an obvious role for Merlin.

If Merlin held such an important role, it would seem that there should be some record of him somewhere. It is strange that Geoffrey makes no record of this. But there is something in Geoffrey that may give us a clue. When Uther dies the noblemen of Britain implored to “Dubricius, Archbishop of the City of the Legions, that is their king he should crown Arthur”. Here was someone with clear authority and the power to anoint kings. Who was Dubricius?

Dubricius (Saint Dubric) is an acknowledged historical person, who in later years was raised to the sainthood. He is claimed to have founded the bishopric at Llandaff, and to have ordained Samson, late Bishop of Dol in Brittany. Some of the recorded dates conflict here. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, Dubricius died in about 612 (his entry states that the date of his death is “the most authentic information we have about him”).

However, Samons’s life is recorded as 480-565. Something is wrong. It may be that because of his later fame, Dubricius’s life became entangled with other great names of history. However, other studies assign different dates to Dubricius, such as The Oxford Dictionary of Saints, which gives his death as about 550, whilst other sources date him even earlier. These dates would not only accord with the dates for Samson, but are remarkably close to Merlin’s supposed life.

Could it be that the character and the role played of Merlin and that of Archbishop Dubricius are one and the same? This is the conclusion that Norma Lorre Goodrich reaches in her books. Certainly it is strange that once Arthur becomes king, Merlin does not appear again in Geoffrey’s History. When we come to the all-important battle of Mount Badon, where Arthur convincingly defeats the Saxons and establishes a peace that lasts for forty years, we find that it is Dubricius who speaks to the troops from the Mount. You might think, considering the reputation that Geoffrey has building for Merlin, that it would have been he who delivered the speech. If he didn’t, where was he?

There could, of course, be plenty of explanations. In real life, Merlin and Dubricius may have been enemies. Dubricius represented the church whereas Merlin, because of his dubious birth and magical arts, represented a pagan culture, synonymous with the Druids. For Arthur to be a Christian king, it would have been impossible for Merlin to crown him or, for that matter, to remain his principal adviser.

There is another interesting point. Tales and legends about Dubricius were abundant at the time that Geoffrey was researching his History. Dubricius’s remains had been discovered on the Isle of Bardsey and translated to the abbey at Llandaff in the year 1120, the same year that a book about him, Lectiones de vita Sancti Dubricii, appeared.

This book, and other writings, gave Dubricius a miraculous birth. Apparently he had no father, but was the son of a nun, herself a granddaughter of King Constantine and thus second cousin to King Arthur. This accords entirely with the supposed origins with Merlin, and it is more than tempting to think that Geoffrey either confused or linked the stories of Dubricius and Merlin.

In book 8 of his History, Geoffrey mentions Dubricius and Merlin in almost the same sentence. He notes the raising of Dubricius to the sea of Caerleon, and he then goes on to describe how Merlin raises the memorial of Stonehenge as a “sepulchre”. It does seem strange that within almost one breath Geoffrey would favour a Christian and then a pagan act. In fact Merlin would seem to be performing a Christian ceremony. However, in book 9, when describing the members of Arthur’s court, Geoffrey makes no reference to Merlin but not only mentions Dubricius as “Primate of Britain”, but attributes him miraculous powers of healing. The last reference to Dubricius tells us that the saintly man had resighed his archbishopric in order to become a hermit, and presumably to devote his final years to solace and prayer. Could this relate to the solitude of Merlin, ensnared as legend says by Vivienne, alone in a cave?

However you consider it there are some remarkable similarities between the roles of Merlin and Dubricius and, as Arthur’s mentor and adviser, they could easily be the same person, regardless of the legends that grew around them in later years.

In which case, why the two names? Dubricius is, of course, a Latin name and not the original Welsh, which was Dyfrig. Dyfrig in Welsh means “waterman”, which might be likened to “baptist”, although in Latin it became confused with “merman”. By a coincidence one translation of the name Merlin was “mermaid”, although the real meaning of the word “mermaid” is maid, or lady, of the mere, or lake! Could it be that, in his name, “Dubricius” or “Dyfrig” was used interchangeably with “Merlin”, or that one or the other was a title or honorific, so that the bishop may have been referred to at times as Dubricius the Merlin; that is, Dubric the waterman or baptist?

Merlin, though, was also a Latin name, the original Welsh being Myrddin, a name which is believed to mean “fortress”. It was, in fact, an ancient and much revered name, possibly attributable to a god. In ancient days, the island of Britain was referred to as the Fortress Isle, or Myrddin’s Isle. It would be no surprise, therefore, to want to link the legendary status of Merlin, or Arthur’s protector, with that of the very matter and origin of Britain itself. And if Dubricius was recognized in this day as the Primate of Britain he may have been termed Dubricius of Myrddin.

Either way there is some substance here which could untangle the tales. It seems more than possible to me that Geoffrey, knowing the stories and legends of Dubricius, and knowing the other names by which he was called, interlaced these with tales he read in his “little book” and developed the story of Merlin, as Britain’s kingmaker, out of the original tales of Dubricius.

Although the actions of one were pagan and of the other Christian, six centuries after their existence these events had become impossibly entwined.

There is one other matter to resolve, though, which may provide an additional explanation, and that is the later life of Merlin, or Myrddin, and his relationship to King Gwenddalou. Here we really run into problems with dates. Gwenddalou died at the battle of Arfderydd (which in Latin translates as Arthuret) which is assigned to the year 573. The Merlin of Vortigern would have been over 120 by then. Our image of Merlin as a white-haired, white-bearded old mage, rather like the near-immortal Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings, might fit the dating, but in all seriousness it is pushing credibility, even with all of the accepted anachronisms.

In his book The Quest for Merlin, Nikolai Tolstoy establishes, certainly to my satisfaction, that this Merlin or Myrddin is a later and distinctly historical person, recognized in the Dictionary of National Biography as Myrddin Wyllt, or Merlin the Wild. Myrddin was a bard and adviser at the court of King Gwenddalou. He was known to the Strathclyde bishop of Glasgow, Kentigern, who lived from 550 to 612. Kentigern was appointed bishop by Riderch, the new king Strathclyde who had defeated Gwenddalou at Arfderydd and was, apparently, threatening to hunt Myrddin down – probably because of poetical propaganda Myrddin had been spreading against him. It was for this reason that Myrddin fled into the forest, having already almost lost his reason because both his king and his brothers had been killed in the battle. W. Rutherford and N. Tolstoy think he may have been a latter-day Druid and so took part in shamanistic practices. Jung and von Franz also see shamanistic elements in the story of Merlin.

Although Geoffrey in his Life of Merlin sought to reconcile these two legends, clearly they cannot be. What is more likely is that in his research for the History of the Kings of Britain, Geoffrey had come across the Prophecies of Myrddin (the sixth-century bard) and had worked them into his story of Dubricius, either because they seemed to fit well with the story of Vortigern, which he had copied from Nennius, or because he genuinely confused Myrddin with an earlier Merlin. As a result, over the centuries, some of the writings and stories associated with the later bard have been grafted on the story of the earlier enchanter and kingmaker.

This is all, of course, supposition, although it’s fairly convincing. If the start from the viewpoint that King Arthur existed, it is not difficult to belive that he would have had a senior adviser, and that that adviser could have been Dubricius. It could also follow that Dubricius became confused with a man of equivalent miraculous powers whom Geoffrey called Merlin, a name he possibly confused with the later bard Myrddin.

It is not surprising that because of, not despite, this confusion, Merlin has become such a fascinating character, with a blending of so many facets: wisdom, madness, good and evil, adviser and schemer. The Arthurian world would be fascinating enough without Merlin: all of those chivalrous and heroic adventures, but add the dimension of magic and mischief provided by merlin, and you have the greatest fantasy on Earth. For near nine hundred years, since Geoffrey unleashed the story of Merlin and Arthur, writers, poets and artists have been fascinated with the life and the legend.

This contrasts with the earlier thory of E. Davies that Merlin was a god (the evening star), and his sister Ganieda a goddess (the morning star). There is some evidence that Merlin may originally have been a god, for in the Triads, we are told that the earliest name for Britain was Merlin’s Precinct, as though he were a god with proprietorial rights. G. Ashe would connect him with the cult of the god Mabon. Because of his association with stags, there may be a connection with Cernunnos, the Celtic horned god.

See also

Conrad | The Legend of King Arthur

Dinabutius | The Legend of King Arthur

Tomb of Merlin

Tombeau de Merlin

According to one version of the legend of Merlin’s imprisonment, he was buried in a neolithic formation of stones leading to an antechamber within the earth.

The famous writer Félix Bellamy spoke of it quite often. He described a covered alleyway, in ruins, of which there still existed eight stones up until 1892. At that date, the owner of the land on which it was located, attracted by the scent of the possible treasure waiting beneath the soil, decided to dig up whatever he could find, scientific discovery be damned. There are few words to describe the effect of this dynamiting, but the evil has been done, irreversibly.

Today, the Tombeau de Merlin is now composed of only two perpendicular slabs of red schist, separated by an old holly tree… a monument which fails to enchant all visitors, a number of whom find it difficult to believe that the mage or archdruid would be content with such a modest tomb!

People come from all over to world to visit this site and sometimes hang wreathes upon the holly tree. It is also noticed that many people had taken clippings of holly from the branches as souvenirs, and the tree is in serious danger of dying.

Located scarcely a few steps away is the Fontaine de Jouvence, where children were presented to the priests to have them washed and entered into the “marith” (register).

Malory puts the place of Merlin’s imprisonment under a stone in Cornwall. I continue to find it unconvincing that the mighty Merlin could not free himself from a spell woven by one of his own students. Other, older versions of the tale have Nimue (or Viviane) retiring Merlin through affection, giving him a retreat of comfort and cheer. It is interesting that White, who loves Merlin and makes him endearing, puts him in cozy retirement in a tumulus on Bodmin Moor, Cornwall, although Nimue is not in evidence to share his society (The Book of Merlyn). Perhaps Merlin requested Nimue to take over the mentorship of Arthur’s court for him; she does appear from time to time in this role throughout much of Malory’s work.

In Vulgate VII, I found what appeared to be a prophecy that either Percivale or Galahad was to rescue Merlin after achieving the Grail, but nowhere else did I uncover a hint of any such deed.

Merlin’s Tomb is the name formerly given a bank of earth at the Camp du Tournoi in Brittany. There are also Merlin’s tombs in Ille-et-Vilaine and Hotie de Viviane.

Literary Origins

Merlin’s appearance in the ancient writings is patchy, for although some events later ascribed to him are referred by Nennius in the ninth century, Merlin himself is not named. The story of Merlin was born fully fledged in the writing of Geoffrey of Monmouth. Geoffrey was a cleric and teacher who lived from about 1100 to 1155, for most of that time being resident in Oxford. He tells us that he was fascinated with the ancient tales of the kings of Britain, but was unable to learn much about them until a friend of his, Walter, the Archdeacon of Oxford, gave him an ancient little book written in Welsh which gave a complete history of the kings of Britain. This Geoffrey chose to translate into Latin. Unfortunately this original book has vanished over the years and it is impossible to know how much Geoffrey derived from that source and how much was either of his own research (probably little) or the product of his own imagination (probably much).

He started his translation around the year 1130. This was a period of much interest in the early tales and legends. A few years earlier William of Malmesbury had produced his Gesta Regum Anglorum, another history of the kings of Britain, which mentioned the deeds of King Arthur, and at the same time Caradoc of Llancarfan was writing his Vita Gildae, the life of S:t Gildas, a monk and contemporary of Merlin. This biography mentions Arthur and Guinevere and makes the first links between Arthur and Glastonbury.

Geoffrey found himself pressured to complete his book, but he was determined to be thorough. In order to satisfy demand, in particular that of Alexander, bishop of Lincoln, Geoffrey hurriedly completed a translation of another text he was consulting, the Prophetiae Merlini, or the Prophecies of Merlin, which he issued in 1134. This text he later incorporated into his major work, the Historia Rigum Britanniae, or the History of the Kings of Britain, which was eventually completed in 1136. It proved instantly popular with a couple of hundred known copies (and probably many more now lost) in circulation before the end of the century. This book, which seeks to give the kings of Britain a pedigree going back as far as 1200 BC and the Fall of Troy, devotes much of its space to the story of King Arthur, which is itself presaged by the story of Merlin. Although throughout the book history and imagination fight for supremacy, the appearance of Merlin seems to have allowed Geoffrey to pull out all the stops and deliver a tale for the telling.

We are in the fifth century Britain. The British king Vortigern, whose name was synonymous with evil and corruption, had invited the armies of the Saxon King Hengist, which had already once been expelled from Britain, back to the island to help fight the Picts. The Saxons took advantage of the situation and Vortigern soon found his kingdom under threat. He fled to the Welsh mountains where he attempted to build a fortress, but no matter how hard he tried the fortress kept crumbling. He consulted his advisers who told him to seek out a boy with no father who should be killed and his blood sprinkled over the site. Vortigern’s soldiers sought high and low and eventually, at Carmarthen, found Merlin, a boy of about eight or nine.

Vortigern learned that Merlin’s mother, though herself of royal birth, was a nun who had been visited by demons or incubi, leading to the birth of Merlin. Merlin was aware of the threats against him, but he not only revealed to Vortigern the reason why his tower could not be built, but also issued his prophecies of the future of Britain.

Merlin remains, thereafter, a schemer. His prophecies begin to come true. Vortigern had previously usurped the throne from King Constantine whose sons, Uther and Aurelianus, had fled to safety in France. Now mature, they return to Britain, besiege Vortigern in his fortress which is set on fire, and the usurper perishes. In celebration Aurelianus, now king, seeks to establish a monument. Uther is despatched to Ireland with Merlin to bring back a massive stone circle, transport it to Britain and resurrects it on Salisbury Plain – Stonehenge.

Aurelianus dies after a short reign and his brother, Uther, becomes king. Merlin now schemes to arrange the birth of Arthur. Uther desires Ygraine, the wife of Gorlois, duke of Cornwall. Merlin conjures up a glamour which transforms Uther into Gorlois and Ygraine, so decieved, welcomes him to her chamber. Thus Arthur is conceived. In making this arrangement with Uther, Merlin had ordained that he would raise the child. It is Arthur’s boyhood with Merlin that forms the basis of T.H. White’s humorous and beguiling novel The Sword in the Stone.

During Uther’s reign the Saxons recommence their incursions into Britain. After Uther’s death, the noble clamour to have Arthur declared king of Britain for, despite his youth, they belive that he is the man to save the island. Geoffrey of Monmouth makes no mention of the incident of the sword in the stone. That appears to be the invention of Robert de Boron who describes how Merlin magically embeds a sword in an envil which is set upon a stone (not in the stone itself) and challenges the nobles to remove it. He who succeeds shall be king. Needless to say, Merlin’s magic ensures that Arthur alone succeeds.

This sword is not the same as Excalibur. Merlin later introduces Arthur to Vivienne, the Lady of the Lake, who gives Arthur the sword. She advices him that the scabbard is more important than the sword, and that provided the scabbard is safe, Arthur will not be defeated. The later plotting of Morgan le Fay ensures that the scabbard is lost and thereafter Arthur’s fate is sealed.

Throughout the early part of Arthur’s reign Merlin is always there, behind the scenes, twisting and shaping events, perhaps to his own advantage, perhaps to Arthur’s. Interestingly, the creation of this role was the job of the later romancers, starting from Robert de Boron, and not Geoffrey of Monmouth. After Arthur has become king, Merlin does not feature again in Geoffrey’s History.

However, after he had completed that work, Geoffrey discovered more about Merlin, or Myrddin in his own language, and in about 1150 published the Vita Merlini, or Life of Merlin. This is a different Merlin from the one described in the History, and Geoffrey may have regretted his haste in completing the earlier work. His later researches had unearthed the story of the British bard, Myrddin, whose name Geoffrey had taken and linked with other legends. Did Geoffrey realize what he had done, or was he just careless in his research? Rather than contradict his earlier work, Geoffrey fudged some of the facts and timescales, and consequently gave us two different portrayals of the character Merlin: one of the kingmaker and magician, the other the poet who descends into madness. The result amongst his readers, though, was not confusion but fascination.

For this later tale, Geoffrey has drawn upon the Gododdin, a poem by Aneinin, a sixth century British bard. In this poem, Merlin is living long after the death of Arthur. He became allied to King Gwenddalou and, after that king’s death at the battle of Arfderydd, Merlin, feeling guilty for not saving his king, suffers bouts of madness, and flees to the Caledonian forest where he lives like a Wild Man.

In the work of the romancers, Merlin’s fate is much more exciting. He falls in love with the beguiling Vivienne, the Lady of the Lake. Having learned his magical craft she lures him to a cave (in other legends a tower or a forest) and there imprisons him. Undying, his spirit remains ensnared down through the centuries.

That, then, is the story of Merlin in its simplest outline. We have a magician, born of demons, who shapes the fate of kings but who falls, himself, for the love of a young girl, and is ensnared by his own magic. Perhaps he lives on, but racked by guilt he flees into the forests where he lives like an animal and becomes mad. Merlin appears as both friend and foe, as representative of good and evil, of paganism and Christianity. He may be wise but he is not someone to be trusted, and in the end he becomes a victim of his own schemes.

Such is the fabric of legend and romance. But was Merlin purely the invention of Geoffrey of Monmouth and Robert de Boron, or was there a real man, or men, behind the tales?

The Name Merlin

Glennie calls Merlin, with Taliesin, Llywarch Hen, and Aneurin, one of the four great bards of the Arthurian Age. I have no reason to doubt this is any other Merlin than the necromancer. It was also in Glennie’s book that I found the tantalizing reference to Merlin’s twin sister, Ganieda.

Spence believes that Merlin’s story became fused with that of Ambrosius Aurelianus, accounting for the mages’ alternate names “Merlin Emrys” and “Merlin Ambrosius”. Merlin was probably more a title or office than a personal name.

Chrétien de Troyes alludes to Merlin exactly once, and then in a context suggesting that the mage may already have been legendary by Arthur’s time: in Erec and Enide appears the observation that in Arthur’s day sterlings had been the currency throughout Britain since Merlin’s time.

See also

Arwystli | The Legend of King Arthur

Image credits

Conception of Merlin | From the prose Lancelot, c. 1494

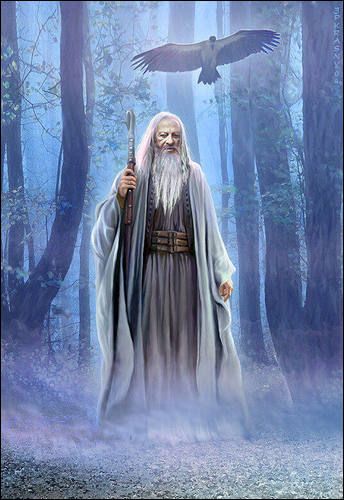

Merlin | Artist: Giacobino, Deviantart

Merlin and Arthur | Artist: Unknown

Merlin the Enchanter | Artist: Unknown

Tomb of Merlin | Photo: Unknown

Sources

Historia Regum Britanniae | Geoffrey of Monmouth, c. 1138

Vita Merlini | Geoffrey of Monmouth, c. 1150

De Principis Instructione | Giraldus Cambrensis, c. 1193

Merlin | Robert de Boron, 1191–1202

Prose Merlin | Early 13th century

Vulgate Lancelot | 1215-1230

Vulgate Merlin | 1220-1235

Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin | 1230-1240

Le Morte Darthur | Sir Thomas Malory, 1469-1470

The Faerie Queene | Edmund Spenser, 1570-1599

King Arthur; or, the British Worthy | John Dryden, 1691

The Life of Merlin | Thomas Heywood, 1641

Idylls of the King | Lord Alfred Tennyson, 1859-1886