‘Boy With No Name’, ‘Knight of Maidens’, ‘Knight of the Surcoat’

Balbhuaidh, Calliano, Calvano, Chalvano, Gagains, Galvagin, Galvaginus, Galwainus, Galwan, Gaoulbanos, Gauain, Gauaine, Gauainet, Gauains, Gauanet, Gauein, Gaugains, Gauuain, Gauvain, Gauvains, Gauvei, Gauvein, Gauveis, Gauwain, Gavain, Gavains, Gavaon, Gaven, Gavion, Gawane, Gawaine, Gawains, Gawan, Gawayne, Gawein, Gawyn, Gawein, Gawen, Gawin, Gayain, Gowin, Grion, Gualguainus, Gualguanus, Gualwanus, Valven, Walewein, Walgan, Walgannus, Waluuanii, Walwain, Walwainus, Walwan, Walwein, Walwen, Walwin, Wawain, Wawayne

The eldest son of King Lot of Orkney and Queen Morgawse (or Anna), Arthur’s sister or half-sister. Brother of Gareth, Gaheris and Agravaine, chief of the Orkney clan (which included his brothers and half brother Mordred), Arthur’s favorite nephew, and one of the most strongest and famous knights of the Round Table.

Celtic Origin and Oral Legend | His Name | Gawaine’s Character | Medieval Literature | Gawaine’s Career

Marriage | Guinevere and Lancelot | Mordred’s Rebellion | Gawaine in Ballads | Beheading Contest

Modern Literature | His Personality | Gawaine – a solar god? | His Grave | Family and Retainers

Celtic Origin and Oral Legend

Like Arthur, the figure of Gawain was born long before the Arthurian legends were written in verse or prose. He comes from the hazy realm of oral tradition, and by the time the Latin Chronicles or the French romances were written, their authors felt it sufficient to simply allude to his adventures. Gawain has no obvious origin in existing early Celtic legend, but he appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s chronicle, and Geoffrey drew his Arthurian characters almost exclusively from Celtic tradition. Another Celtic feature is Gawain’s strength, which supposedly waxed in the morning and waned in the afternoon, indicating that in some murky origin, Gawain may have been a sun deity. He was one of the party picked to help Culhwch in his quest to locate Olwen.

Though his origins are uncertain, Gawain does have two predecessors or counterparts:

- Cuchulainn

An early Irish hero whose adventures – such as the Beheading Game – were assigned to Gawain, in modified form, in French and Middle-English literature. - Gwalchmei

A Welsh hero who, like Gawain, is the nephew of Arthur. Gwalchmei is substituted for Gawain in later Welsh adaptations of French literature.

In Welsh tradition his father is sometimes given as Gwyar, but sometimes Gwyar is said to be his mother. In French he is called variously Gauvain, Gauwain, Gayain, and so on. In Latin he is Walganus (Geoffrey calls him Walgainus), in Dutch Walewein and in Irish Balbhuaidh. He is also possbily to be identified with Uallabh, the hero of a Scottish tale. In Welsh his name is Gwalchmai (‘hawk of May’ or ‘hawk of the plain’). R.S. Loomis argues that Gawain and Gwalchmai were originally different characters and that the Welsh identified their hero Gwalchmai with the Continental Gawain. He suggests that Gawain is in origin the Mabinogion character Gwrvan Gwallt-avwy and that his name may have arisen from Welsh Gwallt-avwyn (‘hair like rain’), Gwallt-afwyn (‘wild hair’) – the sobriquet of the Welsh warrior Gwrfan – or gwallt-advwyn (‘fair hair’). R. Bromwich disagrees and argues that Gawain and Gwalchmai were always identical.

William of Malmesbury (1125) says he was Arthur’s nephew and that he ruled Galloway, which was apparently named after him, and that his grave was discovered in Pembroke in Wales (there seems to be some confusion with an obscure St. Govan, who has a church in Pembroke). On the cathedral archivolt in Modena, Italy, he appears to rescue Guinevere from her abductors, Mardoc and Caradoc.

Geoffrey of Monmouth (c. 1138) sketches a brief biography of his life, naming his parents as King Lot of Lothian and Anna, Arthur’s sister. During the time of Arthur’s conquests, Gawain is raised in Rome, in the service of Pope Sulpicius. He eventually returns to Britain and becomes one of Arthur’s warriors. When Arthur and Rome prepare for war, Gawain is part of a peace envoy sent to the camp of the Roman Emperor Lucius. Gawain takes offense to some comments by one of Lucius’s soldiers, cuts off his head, and starts the war. Gawain dies at Richborough, in the first battle between the forces of Arthur and Mordred, Gawain’s brother.

His Name

Phyllis Ann Karr says: “I have heard his name pronounced both Gah-WANE (rhymes with Elaine) and GAH-w’n. The first seems by far the most popular today, but I prefer the second; I have no scholarly opinion to back me up, but GAH-w’n seems the preferred pronunciation in the dictionaries I have checked, it seems to match the pronunciation of the modern derivative name Gavin, and emphasizing the first syllable seems a better safeguard against aural confusion with such names as Bragwaine and Ywaine.”

Gawayne is a variant spelling that appears in the original title of the famous fourteenth century Sir Gawayne and the Greene Knight.

Gawaine’s Character

Gawain appears to have northern, possibly Scottish, origins, but it is impossible to trace him back to a historical model, however shadowy. Unlike Kay and Bedivere, who have early associations with Arthur in Celtic tradition, Gawain belongs to a later stratum of the Arthurian story, and the Welsh name Gwalchmei is first regarded as the equivalent of Gawain in translations of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae and the Welsh romances. An early mention of Walwanus is to be found in William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum, but he first appears in a role of any importance in Geoffrey of Monmouth. However, occurrences of the name Walwanus (and variants) in charters suggest the poopularity of stories about him in the eleventh century on the Continent. His first significant appearances are in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia and Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval. His character is inconsistent.

Early French romance considered him the pearl of worldly knighthood, but the Vulgate and Post-Vulgate Cycles somewhat besmirched his character, turning him into a brash bully who murders knights during the Grail Quest and contributes to Britain’s downfall by egging Arthur into a war with Lancelot. Middle-English romance rejects this portrayal and again elevates him to the epitome of chivalric virtue, the most famous example being Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Malory, however, follows the Vulgate interpretation and, consequently, Gawain is a less significant character to modern audiences.

Medieval Literature

Gawain made the transition from chronicle to romance in Chrétien de Troyes’s Perceval (c. 1190). Though the romance is primarily about the title character, Gawain’s adventures occupy the last third of the uncompleted manuscript. Already, we find in Chrétien a portrayal of Gawain as a noble knight, quick with his sword – Excalibur – and with the maidens. While Perceval tries to unravel the mysteries of the Grail and to repair his previous blunder at the Grail Castle, Gawain must go to Escavalon to defend himself against a murder charge brought by Guingambresil (Guigambresil). We witness him charm the sister of the king of Escavalon, and then fight his way out of the situation when the king’s guards arrive. Later, we see him kindly championing the little daughter of Duke Tiebaut of Tintagel in a tournament, and winning the tournament through his skill in arms. He endures the vicious tongue of Lady Orgelleuse of Logres, who leads him to Canguin Rock, a mysterious castle inhabited by ladies. He braves the Perilous Bed inside the castle, slays a lion, and apparently ends the castle’s enchantments. Chrétien seems to be contrasting the worldly adventures of Gawain with the spiritual education of Perceval.

Chrétien’s story ends soon afterwards, and it is unclear how or if he intended to draw Gawain into the Grail Quest. Chrétien’s first continuator (c. 1200) focused on Gawain to the exclusion of Perceval, describing Gawain’s visit to the Grail Castle, but other continuators retained Perceval as the Grail hero. A notable exception is Heinrich von dem Türlin (c. 1230), who has Gawain complete the Grail Quest and heal the Fisher King.

In Chrétien’s Le Conte du Graal, Sir Percival encounters a mysterious and wounded knight during his quest for the Holy Grail. The wounded knight is later revealed to be his own cousin, Gawain. After a series of adventures and encounters, Percival comes across a mystical spring with miraculous healing powers. The spring is said to have been created from the blood of a slain serpent and has the power to heal any wound or ailment. Upon discovering the healing spring, Percival uses its powers to bathe and cleanse his cousin Gawain’s wounds, ultimately saving his life. The healing spring proves to be a significant boon in their quest for the Grail and the overall well-being of the knights and subjects they encounter on their journeys.

The specific circumstances of Gawain’s injury are not explicitly mentioned in Chrétien’s version of the story, as the narrative focuses primarily on the adventures of Sir Percival. However, other Arthurian texts and later adaptions provide more details about Gawain’s wound. One popular version is found in the Prose Lancelot, a thirteenth-century prose cycle of Arthurian romances. According to Prose Lancelot, during Gawain’s quest for the Grail, he encounters a mysterious spear-wielding knight. The knight, known as the Knight of the Bleeding Sword mortally wounds Gawain, due to a misunderstanding and an intense jousting match. After the incident, Gawain is taken to a hermitage where he is healed by a holy relic, the “Sangreal,” a vessel believed to have caught the blood of Christ. This event marks the turning point in Gawain’s quest, leading him to reevaluate his actions and the quest for the Holy Grail.

Throughout the thirteenth century – the golden age of French and German Arthurian romance – Gawain appears in dozens of romances, but rarely in his own adventures. Already established as the greatest of Arthur’s knights, Gawain acts as a mentor to young warriors and as a yardstick by which to measure the prowess of other knights. In an often-employed formula, a young knight first arrives at Arthur’s court and enters a tournament or joust to prove his prowess. The hero overthrows most of the Knights of the Round Table, but not Gawain, who fights the hero to a draw. In this manner, authors demonstrated the skill of their characters without having them defeat Arthur’s greatest knight. Some of these young heroes, such as Guinglain and Wigalois, are Gawain’s own sons; Gawain, known as the Knight of Maidens, has multiple amies and, it seems, multiple children.

In Geoffrey of Monmouth, Gawain is a valiant warrior who aids his lord and king in various campaigns. The uncle-nephew (sister’s son) relationship is of particular importance in creating an intimate bond between the two that enables Gawain to function as counselor and putative heir to the throne. In Wace’s adaption of Geoffrey, Gawain has already assumed a courtly aspect and praises the virtues of love and chivalry rather than war. It is Chrétien de Troyes, however, who first allots a major role to Gawain in his romances. Gawain functions as a friend of the hero and as a model whom young knight aspire to emulate. Often, the hero of the romance becomes involved in an undecided combat with Gawain, in Chrétien’s later romances the implication being that the hero is the moral victor. Chrétien seems to take a more critical attitude toward Gawain and the way of life he represents as his career progresses, and particularly in Lancelot and Perceval he is unfavorably contrasted with the hero and made the butt of some burlesque humor. Chrétien seems particularly concernes with Gawain’s blind adherence to custom and frivolous attachment to the opposite sex. Even though Perceval is unfinished, it seems clear that Gawain is bound to fail where Perceval will succeed.

Both the burlesque and the more serious strains are taken up in later Old French romances, the burlesque aspect being prevalent in the post-Chrétien verse romances (e.g., Le Chevalier à l’épée and La Vengeance Raguidel) and the serious criticism coming to the fore in the Grail romances, especially in the Vulgate Queste, where Gawain is depicted as a hardened and unrepentant sinner. In the Prose Tristan, he is an out-and-out murderous villain, no respecter of persons or property. As of this point (ca. 1230), authors wishing to depict Gawain therefore had various choices open to them: they could portray him as a real hero, as a somewhat comic figure, or as a true villain. Later French literature shows him in all of these roles.

Outside France, all authors of Arthurian romances were familiar with the French tradition, and it is interesting to note that the portrayal of Gawain varies geographically. In Germany, he remains by and large the same figure as in France, although Wolfram von Eschenbach in his Parzival is less harsh on him than Chrétien in Perceval; he becomes the hero proper of a lengthy Grail romance, Diu Crône, by Heinrich von dem Türlin. Gawain seems to have enjoyed considerable popularity in the Low Countries, where a special form of the name, Walewein, developed very early; the portrayal of him in Middle Dutch literature (with the exception of some texts directly dependent on French models) is almost uniformly positive, and he is named der avonturen vader (‘the father of adventures’). Why the portrayal of Gawain in some Germanic literatures should be so positive is difficult to say, but the case of Middle English is at least partly explicable. There is in Middle English a marked reluctance to take over any of the negative features of the French Gawain, and Middle English romance in many ways restores Gawain to a position of respect and dignity.

The author of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, for example, shows a Gawain who is almost but not quite perfect. Other texts, such as Syre Gawene and the Carle of Carlyle, portray an unimpeachably courteous and valiant knight, or at least one whose actions are not criticized. One possible explanation for this is that English authors and audiences regarded Gawain as a British hero and that it was considered unseemly to show such a figure in a poor light. A similar tendency is visible in the restoration in English literature of the French Arthur from a weak and indecisive monarch to a great warrior-king. Malory departs from this pattern of favorable treatment of Gawain in Middle English, however, when he follows his sources by presenting Arthur’s nephew in an unflattering role. His lead was followed by Tennyson and most postmedieval writers, though some recent novels, by authors like Gillian Bradshaw, have shown him to better advantage once again.

Curiously, French literature, where Gawain occurs more often than anywhere else, rarely shows him in the role of a real hero, setting out on a quest he is destined to achieve, or falling properly in love. This occurs, however, in some of the transformations mentioned earlier, and it is this flexible, nonhero status in Old French literature (but with heroic potential) that rendered the figure of Gawain so serviceable. Authors could use Gawain as part of a design transformed to their own needs, where he might turn out to be a hero or an adjunct, courteous or not, and so on. But on the whole, despite lapses into frivolous love affairs, the figure of Gawain remains by and large admirable, with the exception of the Vulgate Queste and the Prose Tristan. A wicked Gawain of this kind is after all less useful to authors, for a debased and debauched knight makes neither a good foil for the hero of a romance nor a good hero himself.

Other French romances to feature Gawain include a pair of parodies called La Mule Sans Frein and Le Chevalier à l’Épée, La Vengeance Raguidel (Gawain avenges the murder of a knight named Raguidel against Sir Guengasoain), L’Atre Périlleux (Gawain rescues a maiden kidnapped by Escanor le Beau), Les Merveilles de Rigomer (Gawain conquers Rigomer castle after many of Arthur’s other knights, including Lancelot, fail). Also notable are Heinrich von dem Türlin’s Diu Crône (c. 1230), a German romance that makes Gawain the Grail Hero, and Penninc and Pieter Vostaert’s Roman van Walewein (late thirteenth century), in which Gawain embarks on multiple interlocking quests with the ultimate goal of obtaining the Floating Chessboard from King Wonder.

The great prose cycles written in the early thirteenth century offer the first and only detailed biography of Gawain’s life, intertwined with the epic tale of Arthur’s rise and downfall. This model was to serve as the source of Malory’s Gawain and, consequently, of the modern conception of Gawain. Gawain, though still a significant character, is eclipsed in importance by Lancelot. The Vulgate Queste del Saint Graal is the first romance to make Gawain a sinner; the portrayal in the Post-Vulgate romances is even darker; and in the Prose Tristan, he is thorougly evil.

The father of Gawain was King Lot who, in his early days, was a page to Arthur’s sister, Morgause, on whom he fathered Gawain. He got his name from a hermit who had baptised him and through intercessions given him the ability to, no matter how wounded he was after a battle, he healed and got his strength back at the time for dinner. The boy was set adrift in a cask. (In De Ortu Waluuanii his mother is called Anna rather than Morgause.) He was rescued by fishermen and eventually found his way to Rome where he was knighted by Pope Sulpicius. Arriving at Arthur’s court, he became one of the king’s most important knights. In early romance he is depicted as a mighty champion, though in later stories, for example French tales and Malory whom they influenced, he is less likeable.

J. Matthews points out that the story of Gawain’s birth and his being set adrift in a cask parallels that of his brother Mordred and suggests that originally Gawain was Arthur’s son, who fathered him incestuously on his sister who, in the original story was Morgan Le Fay. The adult Gawain became Morgan’s knight and his story is predated by the mythical tale of the Celtic god Mabon whose mother, Modron (earlier Matrona), is the prototype of Morgan. He also suggests that Galahad replaced Gawain as a Grail quester because of Gawain’s pagan associations. That Percivale similarly replaced Gawain was suggested earlier by J.L. Weston.

Gawaine’s Career

The account given by Vulgate and Post-Vulgate romances is summarized as follows:

Gawain is born to King Lot of Lothian and Arthur’s half-sister (Belisent or Morgause). He is a descendant of Peter, a follower of Joseph of Arimathea. His brothers are Agravain, Gareth, Gaheris, and Mordred. Gawain’s father joins a rebellion against Arthur shortly after Arthur is first crowned. When Gawain, a young man, hears that Arthur is his uncle, he leaves his father’s household and swears never to return until Lot submits to Arthur.

Joined by his brothers and cousins (Galescalain (Galeshin) and the Yvains), Gawain goes to seek out Arthur, who is embroiled in a war against the invading Saxons. Along the war, Gawain and his companions encounter forces of Saxons, which they defeat at the battles of Logres and Diana Bridge, among others. Merlin assists Gawain in these fights. Eventually, Gawain and his companions find Arthur and are knighted for their brave service. Arthur gives Gawain Excalibur when he receives a better sword. Gawain participates in Arthur’s war with Lucius of Rome and begins the first battle as in Geoffrey of Monmouth.

After Arthur has pacified Britain, Gawain has innumerable adventures, some of which are a credit to his character, some of which shame him. He embarks on several quests to find Lancelot, who always seems to be missing. Gawain defends Roestoc against an attack by Seguarades. He supports the true Guinevere during the False Guinevere (Genievre) episode. He is imprisoned for a time by Caradoc of the Dolorous Tower, but is liberated by Lancelot. He becomes king of the Castle of Ten Knights for six years.

He gets into his usual scrapes over women: he is attacked by the king of North Wales after sleeping with the king’s daughter; and he betrays Pelleas by sleeping with Arcade. He allows himself to become ensorcelled by the ladies on the Rock of Maidens and has to be freed by his brother Gaheris. In the Post-Vulgate version, Pellinore has killed Lot, so Gawain and his brothers kill Pellinore and Pellinore’s sons Lamorat and Drian.

Gawain visits the Grail Castle, but is unable to mend the Grail Sword. He is unable to deliver the daughter of King Pelles from her tub of boiling water. In another visit to Corbenic, he sees the Grail, but his eyes are drawn away from the holy vessel to the beautiful maiden carrying it. He is driven from the castle in a cart, surrounded by peasants pelting him with dung.

When the Sword in the Stone arrives at Camelot, Gawain is unable to draw it, and it is predicted that he will receive a wound for having tried. Gawain is the first to announce his commitment to the Grail Quest when the Grail appears to the Knights of the Round Table. During the quest, Gawain, Gaheris, and Yvain kill the seven brothers whom Galahad has exiled from the Castle of Maidens. In other adventures, Gawain kills his cousin Yvain the Bastard, King Bagdemagus, and sixteen other knights. He is told by a hermit that he cannot achieve the Grail because he lacks humility, patience, and abstinence. Eventually, he is wounded by Galahad in a tournament (by the same sword that Gawain had tried to draw from the stone) and is laid up for the rest of the quest. Afterwards, Arthur chastises him for having killed so many knights during a holy quest.

Gawain remains neutral during the discovery of Lancelot’s affair with Guinevere until Lancelot accidentally kills Gaheris and Gareth while rescuing Guinevere from the stake. Gawain’s fury forces Arthur into a war with Lancelot, and Gawain refuses any compromise or surrender or apology from Lancelot. Finally, in Benoic (Benwick), he fights Lancelot in single combat and receives a serious head wound. The Romans attack Arthur while Arthur is in France, and Gawain’s wound is aggravated during the battle. Arthur’s army returns to Britain to deal with Mordred’s treachery. Gawain, on his deathbed, relents and says,

I am sadder about not being able to see Lancelot before I die than I am about the thought of dying. If I could only see the man I know to be the finest and most courteous knight in the world and beg his forgiveness for having been so uncourtly to him recently, I feel my soul would be more at rest after my death.

Gawain perishes of his wound a few days later and is buried in a tomb with his brother Gaheris.

Though this version of Gawain’s life and character survives in Malory (1470), Gawain briefly reclaims his heroic, pure status in the Middle English romances of the fourteenth century. These include Syre Gawene and the Carle of Carlyle (by passing a test of nobility, Gawain transforms the Carl of Carlisle and marries his daughter), The Avowing of King Arthur (Gawain rescues a maiden from Menealf), The Awntyrs off Arthure (Gawain defeats Lord Galleron of Galloway in a battle before Arthur), The Weddyng of Syr Gawen and The Marriage of Sir Gawain (Gawain marries the Loathly Lady (Dame Ragnell) in order to save Arthur), and, of course, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, in which Gawain demonstrates virtues while braving a beheading game at the hands of the supernatural Green Knight.

Again, Malory, using the Post-Vulgate characterization, makes Gawain a knight whose human failings are all too evident, though his final letter of forgiveness to Lancelot

By a more noble man might I not be slain

is a magnanimous and moving moment. Gawain is not the main character in any of Malory’s eight books, though some of them feature Gawain chapters. The ultimate effect of Malory’s treatment was to relegate Gawain to second-class status. In later romances, including modern fiction and film, Gawain’s character is eclipsed by the Lancelot-Guinevere affair. Tennyson mentions him only briefly.

Among these romances, we have, for the first time, two accounts of Gawain’s youth: Les Enfances Gauvain and De Ortu Waluanniii Nepotis Arturi, which are apparently based on Geoffrey of Monmouth’s assertion that Gawain was raised in the service of Pope Sulpicius:

Born illegitimately in the court of Uther Pendragon, Gawain was sent away by his mother in order to avoid any potential problems. She gave him to a knight named Gawain the Brown, who baptized the infant with his name. With only a ring and parchment attesting to his lineage, the infant Gawain was handed to some wealthy merchants (or rescued by fishermen), who took him to Gaul. Leaving him alone on their ship, they docked and entered the town of Narbonne. A poor fisherman named Viamundus happened along, plundered the ship, and took Gawain with him. In time, he journeyed to Rome and raised Gawain there, in the service of the Roman Emperor and Pope Sulpicius. Ignorant of his parentage and true name, Gawain was first called the Boy with No Name and then the Knight of the Surcoat. Knighted by the Emperor of Rome, Gawain claimed the right to the next single combat against Rome’s enemies, and was accordingly sent to Jerusalem when Rome went to war with Persia. On the way, the Roman fleet was blown off course and landed on a barbarian island, where Gawain and the Romans defeated the barbarian King Milocrates. Continuing to Jerusalem, he defeated the Persian warrior Gormundus and settled the dispute.

Having thus served Rome, Gawain decided to journey to the court of the famous King Arthur. The Roman Emperor gave him a box containing the ring and parchment, which he was to present to King Arthur without opening himself. After Gawain defeated Arthur in a joust near his court in Caerleon, Arthur begrudgingly told Gawain that he could join his court if he proved himself worthy. Gawain soon had the chance when Arthur set out to liberate the Castle of Maidens, and Gawain proved himself the only knight able to defeat the pagan king who had captured it. Following this service, Arthur rewarded Gawain by informing him of his name and lineage, and by welcoming him into his service as his knight and nephew.

These are some highlights of his career according to Malory: he first came to court with his mother and three full brothers between the two early rebellions of the petty British kings against Arthur. He seems to have returned about the time of Arthur’s marriage and the establishment of the Round Table, when he asked and received Arthur’s promise to make him knight – they had now learned of their uncle-nephew relationship. At Arthur’s wedding feast, Gawaine was sent, by Merlin’s advice, on the quest of the white hart. On this quest, he accidentally slew a lady who rushed between him and her lord, whom he had just defeated in battle and was about to behead; for this his brother Gaheris, then acting as his squire, rebuked him severely, and Guenevere ordained that Gawaine should

for ever while he lived... be with all ladies, and... fight for their quarrels.

When the five kings of Denmark, Ireland, the Vale, Soleise, and Longtains invaded Britain, Gawaine, Griflet, and Arthur followed Kay’s example to strike them down and save the battle. After this campaign, Gawaine was elevated to the Round Table on King Pellinore’s advice. Nevertheless, Gawaine later slew Pellinore in revenge for Lot’s death (though Malory only alludes to the incident without describing the scene).

When Arthur banished Gawaine’s favorite cousin, Ywaine, on suspicion of conspiracy with his mother, Morgan le Fay, Gawaine chose to accompany Ywaine. They met Sir Marhaus and later the three knights met the damsels “Printemps, Été, and Automne” in the forest of Arroy. Leaving his companions to make the first choice of damsels, Gawaine ended with the youngest (who, however, left him and went with another knight). It was on this adventure that Gawaine became involved in the affair of Pelleas and Ettard, playing Pelleas false by sleeping with Ettard, for which cause

Pelleas loved never after Sir Gawaine.

These adventures lasted about a year, by the end of which time Arthur was sending out messengers to recall his nephews. In Arthur’s continental campaign against the Roman emperor Lucius, Gawaine and Bors de Ganis carried Arthur’s message to Lucius, to leave the land or else do battle. When Lucius defied Arthur’s message, hot words passed on either side, culminating when Gawaine beheaded Lucius’ cousin Sir Gainus in a rage, which forced Gawaine and Bors to take rather a bloody and hasty leave.

Malory seems to insinuate that Gawaine was accessory to Gaheris’ murder of their mother, though

Sir Gawaine was wroth that Gaheris had slain his mother and let Sir Lamorak escape.

Certainly Gawaine was with his brothers Agravaine, Gaheris, and Mordred when they later ambushed and killed Morgawse’s lover, Lamorak, for which Gawaine seems to have lost Trimstram’s (Tristan) goodwill. Despite Gawaine’s vengefulness, however, Lancelot, who had once rescued him from Carados of the Dolorous Tower, remained his friend until the end.

At the time of Galahad’s arrival in Camelot, Gawaine reluctantly, and at Arthur’s command, was the first to attempt to draw Balin’s Sword from the floating marble; shortly afterward, it was Gawaine who first proposed the Quest of the Holy Grail, in the midst of the fervor which followed the Grail’s miraculous visit to court.

Gawaine rather quickly tired of the Quest, however, and had very bad fortune on it besides; in addition to being seriously wounded himself by Galahad, in divine retribution for having attempted to draw Balin’s Sword, he slew both King Bagdemagus and Yvonet li Avoutres – the latter and apparently the former also by mischance in friendly joust.

Sir Gawaine had a custom that he used daily at dinner and at supper, that he loved well all manner of fruit, and in especial apples and pears. And therefore whosomeever dined or feasted Sir Gawaine would commonly purvey for good fruit for him.

Sir Pinel le Savage, a cousin of Lamorak’s, once tried to use this taste to avenge Lamorak, by poisoning the fruit at a small dinner party of the Queen’s.

Marriage

He married in various tales Ragnell, Amurfine, the daughter of the Carl of Carlisle and the daughter of the king of Sorcha. In Walwein he became the husband or lover of Ysabele, while in Italian romance he was said to be the lover of Morgan’s daughter, Pulzella Gaia. Gawaine had

three sons, Sir Gingalin, Sir Florence, and Sir Lovel, these two were begotten upon Sir Brandiles' (Brandelis) sister.

See also

Gawaine’s Wife | The Legend of King Arthur

Guinevere and Lancelot

Gawaine was not party to Agravaine and Mordred’s plotting against Lancelot and the Queen; indeed, Gawaine even warned his brothers and sons against what they were doing. When Lancelot killed Agravaine and all three of Gawaine’s sons in escaping from Guenevere’s chamber, Gawaine was ready to forgive all their deads, and pleaded earnestly with Arthur to allow Lancelot to defend Guenevere and prove their innocence in trial by combat.

Not until Lancelot slew the unarmed Gareth and Gaheris in rescuing Guenevere from the stake did Gawaine feel bound to take vengeance, in pursuit of which vengeance he stirred Arthur besiege Lancelot first in Joyous Garde and later, after the Pope had enjoined peace in Britain, in Lancelot’s lands in France. Gawaine would continually challenge Lancelot to single combat; Lancelot would defeat but refuse to kill Gawaine, who would challenge him again as soon as his wounds were healed.

Mordred’s Rebellion

Learning of Mordred’s usurpation, Arthur returned to England, to meet Mordred’s resistance at Dover; in this battle, the wounds Gawaine had recieved from Lancelot broke open fatally. Between making his last confession and dying, Gawaine wrote a letter to Lancelot, asking his prayers and forgiveness and begging him to hurry back to England to Arthur’s assistance. His death took place at noon, the tenth of May, and

then the king let inter him in a chapel within Dover Castle; and there yet all men may see the skull of him.

His ghost appeared to Arthur in a dream the night of Trinity Sunday, accompanied by the ladies whose battles he had fought in life. In the dream Gawaine warned Arthur to avoid battle with Mordred until after Lancelot had arrived.

These are not all of Gawaine’s adventures even according to Malory, and a recapitulation according to earlier sources would be far more favorable to the famous knight. Malory did not seem to like him, making him a rather unpleasant personality and not even all that impressive a fighter, when compared with other great champions, being defeated by Lancelot, Tristram, Bors de Ganis, Percivale, Pelleas, Marhaus, Galahad, Carados of the Dolorous Tower, and Breuse Sans Pitie. Presumably Lamorak, Gareth and others could also have defeated him, had he finished a fair fight with them. (Once, indeed, he did fight Gareth unknowingly, but left off at once when Lynette revealed Gareth’s identity.)

Gawaine in Ballads

Another story concerning Gawain comes from the vicinity of Carlisle during the days when Arthur was alleged to have held his court there, and is related in a traditional Border ballad. Outside the city walls Arthur was overpowered by a local knight who spared his life on the condition that within a year he would return with the answer to the question “What is it that women most desire?”

No one at his court could supply the answer, so Arthur was honour-bound to return to the knight when the year had elapsed and forfeit his life. On his way to the meeting, Arthur was approached by a hideous woman who told him that she would give him the answer, provided the King found a husband for her. Arthur agreed, and the hag told him that the one thing women desire most is to have their own way. The answer was related to the knight and, proving correct, Arthur’s life was spared. Returning to his court, he appointed Sir Gawain to be the ugly woman’s husband, thus fulfilling his promise.

Though she was hideous beyond comprehension, Gawain always treated her with knightly courtesy, and in return the woman offered Gawain a reward. She would become beautiful either by day or by night, the choise was his. Remembering the answer she had given Arthur, Gawain told her that she might have her own way and bade her choose for herself. His chivalrous answer broke the enchantment under which she had been held, and she immediately became beautiful by both day and night.

See also

Dame Ragnell | The Legend of King Arthur

Gawaine’s Wife | The Legend of King Arthur

The Beheading Contest

The story of the beheading contest which features in the tales of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Gawain and the Carl of Carlisle and Turk and Gawain (see Gromer) has a parallel in Irish mythology where Cu Roi, King of Munster, proclaimed Cú Chullain champion of Ireland. The decision was rejected by two other champions, so Cu Roi arrived in the guise of a giant at Emhain Macha (modern Navan Fort) where the King of Ulster had his court, and challenged each of the three to behead him, on condition that he could afterwards do the same to them. Each of Cú Chullain’s rivals tried but, when the head was sliced off, Cu Roi replaced it and neither of them would let him have his turn.

When Cú Chullain cut off Cu Roi’s head and once again the latter replaced it on his shoulders, Cú Chullain was prepared to let him strike him as agreed, whereupon Cu Roi disclosed who he was and declared Cú Chullain unrivalled champion. The similarity of these tales may indicate a common source, or even that Gawain is identical in origin with Cú Chullain as the tales about him may be indigenous to the north of England; in ancient times, the north-west of England contained a tribe called the Setantii, while the original name of Cú Chullain was Sétanta. It may well have been that Cú Chullain was a Setantii hero with a reputation on both sides of the Irish Sea, whose memory was kept alive under the name of Gawain by the medieval descendants of the Setantii in England.

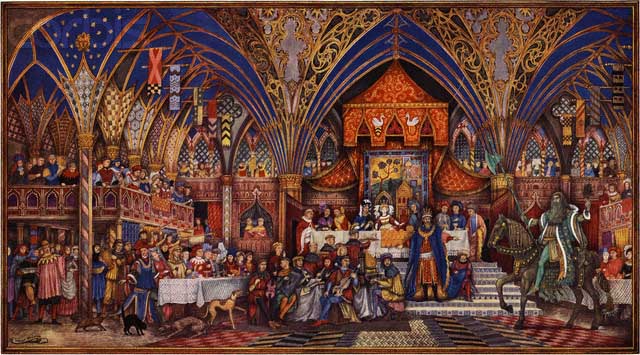

During Arthur’s Christmas Feast the festivities were interrupted by the arrival of a Green Knight, who callenged the knights present to cut off his head, setting as the only condition that he be allowed to retaliate in the same manner the following year. Only Gawain dared accept the challenge.

See also

Beheading Game | The Legend of King Arthur

Modern Literature

Modern treatments are based largely on Malory. By the time we reach Tennyson, Gawaine’s courtesy had degenerated into smooth talk and his chivalry into casual love affairs. William Morris turned him from one of Guenevere’s most ardent defenders into one of her chief accusers. Edward Arlington Robinson retained the superficiality of Tennyson’s character. John Erskine seems simply to have accepted this version of Gawaine as a matter of course. Hal Foster, while making him a major and generally likable character in Prince Valiant, tends to emphasize his lightness and lady-killing qualities. T.H. White, while generally not unsympathetic, turned him into a rather brusque personality and even gave the adventure of the Green Knight to Gareth instead.

It remained for Monty Python and the Holy Grail to sink Gawaine to his lowest point yet: in a line that goes by so fast you’re likely to miss it; Gawaine is named as one of the knights slain by the vicious white rabbit! Vera Chapman created a second Gawaine, nephew and namesake of the more famous, rather than attempt to rehabilitate Malory’s character. One of the few exceptions to the modern picture of Gawaine is Sutcliff’s, in Sword at Sunset, and her Gwalchmai seems to owe as little to the pre-Malory Gawaine s to the post-Malory one.

Once, however, before his place was usurped by Lancelot, Gawaine was considered the greatest of all the knights, the epitome both of prowess and courtessy, the touchstone against whom all others must prove themselves. This is the Gawaine we find in Chrétien de Troyes.

Chrétien’s first romance, Erec and Enide, names Gawaine as one of his uncle Arthur’s most prudent counselors, and gives him as first of all Arthur’s good knights in the roll call beginning at line 1691.

In Chrétien’s next romance, Cligés, Gawaine is much impressed by the titular knight’s performance during the first three days of the Oxford tournament, and decides to open the last day’s combat himself. He modestly says that he fully expects to have no better luck than Sagramore, Lancelot, and Percivale in tilting against the still-unknowing champion, but thinks he may fare better in the sword play: at this stage of the legend, nobody has ever beaten Gawaine at swordfighting.

When the combat comes, Gawaine and Cligés knock each other from their horses, then fight with swords until Arthur calls a halt while the outcome still remains undecided. Gawaine is delighted to learn that he is the young champion’s uncle, his sister Soredamors having married Cligés father Alexander.

In Chrétien’s Lancelot, Gawaine accompanies his good friend Lancelot part of the way on their journey to King Badegamu’s Gore. When Lancelot rides in the cart for the sake of getting to the queen, Gawaine declines the dishonor and follows along on his horse; later, when Lancelot insists on sleeping in the forbidden Deadly Bed, Gawaine quietly accepts the lesser bed his hostess offers him. My own reading of these episodes is that Gawaine shows greater prudence in the first and greater modesty in the second.

Other interpretations are certainly possible, and it might be argued that Lancelot’s success in crossing the Sword Bridge and Gawaine’s failure in crossing the Water Bridge can be traced to Lancelot’s riding in the cart and Gawaine’s refusal to do so; also it would have shown greater courtesy and generosity on Gawaine’s part, when offered him the choice by his friend, to take the Sword Bridge and leave the comparitevly less hazardous Water Bridge to Lancelot.

On the other hand, Gawaine has not, like Lancelot, ridden two horses (one of them borrowed) to death and left himself without a mount and therefore in need of the ignominous cart ride; while, as to the one’s success and the other’s failure to cross the bridges into Gore – if Gore is indeed a branch of the eschatological Otherworld, I might venture the very tentative theory that Lancelot’s desire for Guenevere renders him, in some spiritual sense, already dead. This might make the next world more accessible to him than to the still vital and generally viruous Gawaine, who, while already displaying amorous tendencies, seems to restrict them to more available ladies – for instance, the lively Lunette of Yvain, which can be called a companion piece to Lancelot. In Yvain, Chrétien tells us of yet another sister of Gawaine’s, whom Phyllis Ann Karr call for convenience “Alteria” in her book The Arthurian Companion.

Chrétien’s last and unfinished romance, Perceval, gives us our fullest view of the author’s approach to this hero: at about line 4750, the emphasis twists over from Percivale to Gawaine and, except in one short episode, stays there until Chrétien laid down his pen. Here we see several instances of Gawaine’s modesty, or prudence, with his name: he never refuses to give it when asked outright, but rarely if ever volunteers it, and sometimes requests those he meets not to ask his identity for a certain period of time.

See also

Lady of the Deadly Bed | The Legend of King Arthur

Castle of the Deadly Bed | The Legend of King Arthur

Perilous Bed | The Legend of King Arthur

Wondrous Bed | The Legend of King Arthur

His Personality

He has superior medical and herbal knowledge. We get a flashback glimpse of him acting as judge or magistrate – perhaps filling in for his royal uncle? – meting out strict justice to uphold Arthur’s laws, yet incapable of understanding why one so chastized should harbor a grudge against the judge. We find him carrying Excalibur. We learn that the poor love him for his generosity, and we watch him put his own concerns at risk in order to please a child, the Maid with Little Sleeves, whom he treats like as courteously as if she were fully grown.

At the same time, we see his flirtatiousness in full swing with the young King of Escavalon’s sister, and we find hanging over his head at least one and possibly two charges of murder. The likeliest explenation I see is that all such charges refer to men slain in honest battle (Gawaine stands ready to defend himself in trial by combat), and a similar charge is raised against his cousin Ywaine over the death of Esclados the Red. In Perceval, Gawaine finds himself again in what may well be an outpost of the Otherworld – the Rock of Canguin, where he meets his grandmother Ygerne, his mother (here unnamed), and the sister, Clarissant, he never knew he had. Before learning who they are, he answers the old queen’s questions concerning King Lot’s four sons (without revealing that he is himself the oldest of them, Gawaine gives the same list we have from later sources), King Uriens’ two Yvains, and King Arthur’s health.

As early as Chrétien’s pages we also meet Gawaine’s great charger Gringolet, whom later romancers retained long after they appeared to have forgotten Gawaine’s sisters. As I recall, in ‘Gawaine at the Grail Castle’, Jessie Weston suggests that in now-lost versions of the story, Gawaine may have achieved the Grail.

The Gawaine of Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight is certainly an idealistic young knight very nearly as worthy, pure, and polite as mortal can be – though I must add, in fairness, that critical opinion is divided as to whether the sexual mores of the Gawaine in this poem reflect the general character of the Gawaine of other early romances, are a conscious deviation from the tradition on the part of an individual author, or even have anything to do with his behaviour toward Sir Bercilak’s (Bertilak) wife, whom he refuses, by this theory, through refusal to betray his host’s hospitality. For an excellent study of Gawaine’s pre-Malory character, at least in the English romances, see The Knightly Tales of Sir Gawaine, with introductions and translations by Louis B. Hall.

Even as late as the Vulgate, Gawaine is definitely second only to his close friend Lancelot as the greatest knight of the world (excluding spiritual knights like Galahad). In this versin Gawaine comes across as much steadier and more dependable than Lancelot, much less prone than Lancelot to fits of madness, to berserk lust in battle, to going off on incognito adventures for the hell of it without telling the court in advance, or to settling down uninvited in somebody else’s pavilion and killing the owner in his return.

Gawaine – a Solar God?

The Vulgate tells us that Arthur made Gawaine constable of his household and gave him the sword Excalibur for use throughout his life. For a time, as Arthur’s next of kin and favorite nephew, Gawaine was named to be his successor. Gawaine was well formed, of medium height, loved the poor, was loyal to his uncle, never spoke evil of anyone, and was a favorite with the ladies. Many of his companions, however, would have surpassed him in endurance if his strength had not doubled at noon. In the Vulgate , when Gawaine appears in Arthur’s dream, he comes not with ladies and damses exclusively, but with a great number of poor people whom he succored in life.

The romancers seem agreed on the fact of Gawaine’s strength always doubling or, at least, being renewed at noon.

Then had Sir Gawaine such a grace and gift that an holy man had given to him, that every day in the year, from underne [9.00 am] till high noon, his might increased those three hours as much as thrice his strength... And for his sake King Arthur made an ordinance, that all manner of battles for any quarrels that should be done afore King Arthur should begin at underne. [Malory XX,21]

Modern scholars seem satisified that this is because Gawaine was originally a solar god. The Vulgate gives a more Christian explanation, alluded to by Malory: the hermit who baptized Gawaine and for whom the child was named prayed for a special grace as a gift to the infant, and was granted that Gawaine’s strength and vigor would always be fully restored at noon. For this reason many knights would not fight him until afternoon, when his strength returned to normal. Sometimes the reason for Gawaine’s noon strength is described as being kept a secret; the fact, however, must have become obvious early in Gawaine’s career. Nor was Gawaine the only knight to enjoy such an advantage; Ironside’s strength also increased daily until noon, while Marhaus’ appears to have increased in the evening.

Also among the numerous ladies whose names are coupled with that of Gawaine are Floree, who may be identical with Sir Brandiles’ sister, and Dame Ragnell, his favorite wife and the mother of his son Guinglain (surely identical with Gingalin) according to ‘The Wedding of Sir Gawaine and Dame Ragnell’, which mentions that Gawaine was often married (and presumably, often widowed) – which is one way to reconcile the various tales of his loves and romances.

In Hughes’ The Misfortunes of Arthur, Gawain survives until the battle of Camlann. The Middle English Parlement of the Thre Ages is unique in saying that Gawain survived the Mordred wars and threw Excalibur into a lake.

His Grave

William of Malmesbury says his grave was discovered at Rhos, a place which cannot be identified with certainty, in the reign of King William II (1087-1100).

Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur says he was buried in a chapel in Dover Castle.

And so at the hour of noon Sir Gawaine yielded up the spirit; and then the king let inter him in a chapel within Dover Castle; and there yet all men may see the skull of him, and the same wound is seen that Sir Launcelot gave him in battle.

See also

Gawaine and the Green Knight | The Legend of King Arthur

Gawaine’s Chessboard Shield and Ivory Pieces | The Legend of King Arthur

Gawaine’s Girdle | The Legend of King Arthur

Gawaine’s Herb | The Legend of King Arthur

Gawaine’s Shield | The Legend of King Arthur

Gawaine’s Wife | The Legend of King Arthur

Guenevere and the Poisoned Apple | The Legend of King Arthur

Sir Gawaine’s Family and Retainers

Father

King Lot of Lothian: Jascaphin in Diu Crône

Mother

Arthur’s sister, variously called Albagia, Anna, Belisent, Morgause, Orchades, Sangive, Seife

Brothers

Agravaine, Aguerisse, Beacurs, Gaheris, Gareth, Gwidon

Half-brother

Mordred

Sisters

“Alteria”, Clarissant, Cundrie, Elaine, Itonje, Soredamors, Thenew(?)

Wives, paramours and flirtations

Amie, Amurfina, Arcade, Beauté, Blanchandine, Blanchemal, Bloiesine, Ettard, Flori, Florée, Guenloie, Guilorete, Gwendolen, Helaés, Helain de Taningues’ sister, Hellawes, the Lady of Roestoc(?), the Lady of Beloe, Lady of the Deadly Bed, Lore de Branlant, Lorie, Lunette, the King of Norgales’ daughter, Orguelleuse, Pulzella Gaia, Ragnelle, Tanrée, Venelas, Ydain

Special case

The Maid with Little Sleeves

Sons

Beaudous, Florence, Guinglain, Henec Suctellois, Lionel, Lovell, Wigalois

Uncle

Arthur

Aunts

Elaine of Tintagil, Morgan le Fay

Baptizer (godfather)

Hermit Gawaine

Father-in-law?

King Alain of Escavalon

Brother-in-law?

Brandiles

Brothers-in-law

Gringamore (by the marriages of Gaheris and Gareth); Alexander of Greece ( by the marriage of Soredamors); unnamned husband of “Alteria”

Sisters-in-law

Laurel (married to Agravaine), Lynette (married to Gaheris), Lyonors (married to Gareth)

Nephews

Melehan, Cligés, “Alteria’s” six sons, Saint Kentigern?, Ider?

Niece

“Alteria’s” daughter

Cousins

Ywaine (by Morgan), Galeshin (by Elaine), Edward of Orkney, Sadok

Squire

Eliezer

Ally

Lady of Briestoc

Charger

Gringolet

Image credit

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight | Artist: William McLaren

Sources

The Modena Archivolt (Italian sculpture) | 1120-1140

Gesta Regum Anglorum | William of Malmesbury, 1125

Historia Regum Britanniae | Geoffrey of Monmouth, c. 1138

Roman de Brut | Wace, c. 1155

Erec | Chrétien de Troyes, late 12th century

Cligés | Chrétien de Troyes, late 12th century

Yvain, or Le Chevalier au Lion | Chrétien de Troyes, late 12th century

Perceval, or Le Conte del Graal | Chrétien de Troyes, late 12th century

First Continuation of Chrétien’s Perceval | Attributed to Wauchier of Denain, c. 1200

Wigalois | Wirnt von Grafenberg, early 13th century

Garel von dem blühenden Tal | Der Pleier, 1240-1270

Beaudous | Robert de Blois, mid to late 13th century

Historia Meriadoci Regis Cambrie | Late 13th century

Ywain and Gawain | 1310–1340

The Stanzaic Le Morte Arthur | 14th century

The Awntyrs off Arthure at the Terne Wathelyn | Late 14th century

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight | c. 1400

Syre Gawene and the Carle of Carlyle | c. 1400

Alliterative Morte Arthure | c. 1400

”The Marriage of Sir Gawain” | 15th century

The Wedding of Sir Gawain and Dame Ragnell | 15th century

Le Morte Darthur | Sir Thomas Malory, 1469-1470

”King Arthur and King Cornwall” | 16th century

The Misfortunes of Arthur | Thomas Hughes, 1587

The Masque of Gwendolen | Reginald Heber, 1816

Idylls of the King | Lord Alfred Tennyson, 1859-1886